2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

Aloha ʻĀina: SWCA’s Approach to Managing Invasive Species in Hawaiʻi

Aloha ʻĀina is a Hawaiian phrase that translates to “love of the land.”

Renowned for its breathtaking natural beauty and rich cultural heritage, Hawaiʻi is a unique archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean. Shaped by its volcanic origins, Hawaiʻi features diverse terrestrial and marine habitats, ranging from lush rainforests and towering mountains to pristine beaches and vibrant coral reefs. These islands host a wide range of ecosystems with an exceptionally high level of endemism, meaning the majority of native species are found nowhere else on Earth.

Hawaiʻi’s unique environment, rich biodiversity, and geographic isolation make it especially vulnerable to invasive pests. Because the native flora and fauna evolved in extreme isolation, without the presence of terrestrial mammals, they are highly susceptible to introduced species. These invaders often spread quickly, outcompeting native plants and destroying habitat for native wildlife.

Although Hawaiʻi accounts for less than 1% of the U.S. landmass, it is home to over 40% of the nation’s threatened and endangered species (according to The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation) and is often referred to as the extinction capital of the world. Invasive species not only threaten native Hawaiian ecosystems—they also increase the frequency and severity of wildfires, accelerate soil erosion and landslides, pose risks to human health, and contribute to the loss of culturally significant species.

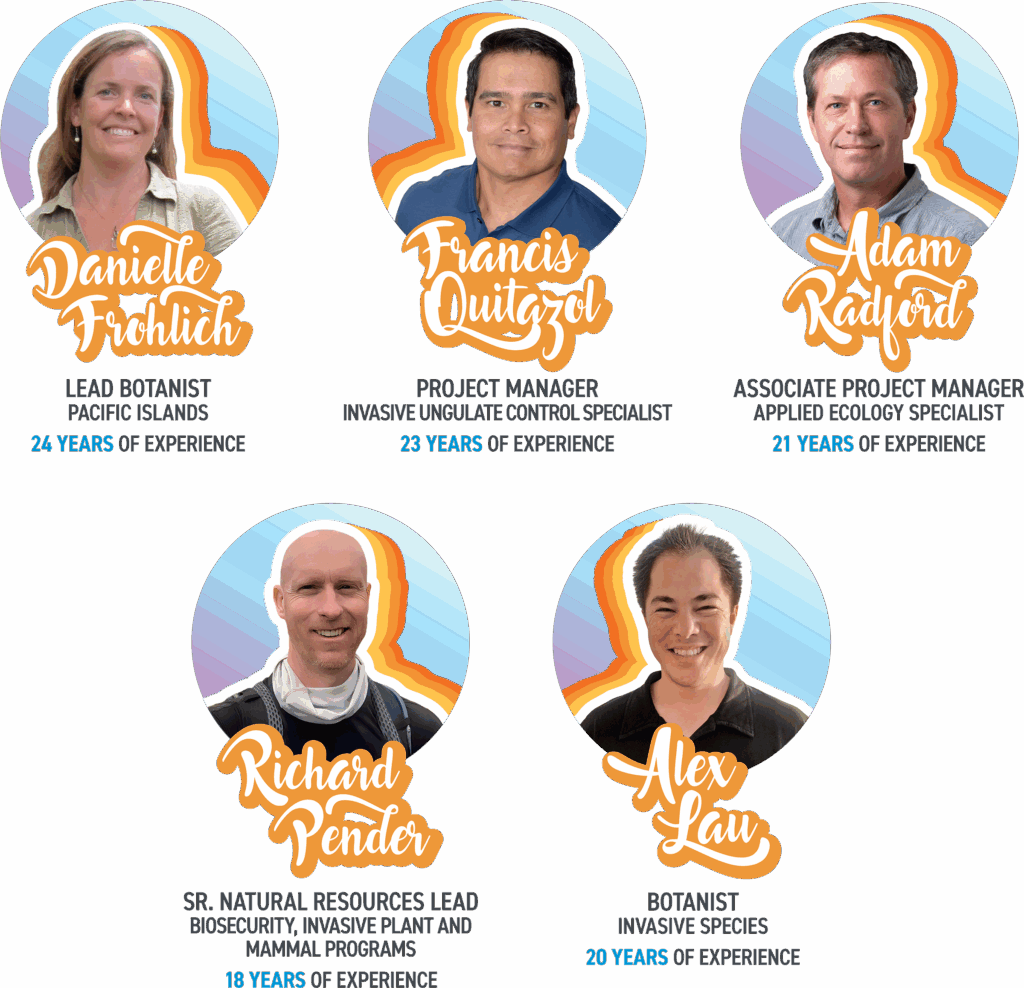

Managing invasive species in Hawaiʻi is no easy feat; it takes collaboration and persistence. Ask any one of SWCA’s experts on invasive species management in Hawaiʻi—Danielle Frohlich, a lead botanist for the Pacific Islands; Adam Radford, an associate project manager specializing in applied ecology; Francis Quitazol, a project manager specializing in invasive ungulate control; Alex Lau, an invasive species botanist; and Richard Pender, a senior natural resources team lead with experience managing biosecurity programs and invasive plant and mammal programs.

With more than 100 years of combined experience working on invasive species issues in the Pacific, this SWCA team brings a wealth of knowledge and collaborative connections to invasive species and land management challenges.

We recently sat down with Danielle and Adam to learn more about invasive species management in Hawaiʻi. Both University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa graduates, Danielle and Adam have a deep passion for mālama ʻāina, caring for and honoring the land.

The Hawaiʻi Invasive Species Council defines invasive species as organisms that are harmful to the environment, economy, and/or human health, and not native to Hawaiʻi. It’s important to note that what is considered invasive in Hawaiʻi may not be considered invasive elsewhere. While there are hundreds of invasive species in Hawaiʻi, some notable examples include:

As you can see, even though commonly thought of as weeds or plants, invasive species encompass insects and mammals too. When managing invasive species in Hawaiʻi, it’s critical to understand the various species and their presence on each island.

“Our surveys extend beyond plants. We actively look for the little fire ant as well as signs of coconut rhinoceros beetles, whose presence is increasingly noted on islands beyond Hawaiʻi Island and Oʻahu, respectively, where these species were first reported. We also monitor for small Indian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) and coqui frogs (Eleutherodactylus coqui), tailoring our efforts to the unique concerns of each island,” explained Frohlich. “As surveyors, understanding the specific invasive threats on each island is crucial. For instance, while mongoose sightings are routine on some islands, they are significant on Kaua‘i,* where we diligently report any occurrences.”

*Small Indian mongoose is believed to be absent from Kaua‘i, although occasional accidental introductions have occurred in recent decades. Ensuring they do not establish on the island is imperative in protecting native ground nesting waterbirds and seabird populations on the island.

Surveying for the little fire ant. Photo credit: Melody Euaparadorn of the Hawaiʻi Ant Lab.

“With the decline of large-scale agriculture in Hawaiʻi over the past several decades, many fields have been left fallow, becoming overrun by non-native grasses and creating a landscape that seems ready to ignite at any moment,” said Radford. “On Maui, a notoriously windy island, these conditions pose a significant wildfire risk, as fires igniting in the grasslands spread quickly and are incredibly difficult to control, as was seen in the catastrophic fires of 2023.”

But it’s not just Maui. In Waimea, on Hawaiʻi Island in late July 2021, wildfire swiftly spread across approximately 44,000 acres, consuming several homes. In response, fuel breaks were implemented (i.e., areas cleared of vegetation) along approximately 37 miles on state and private lands. These roadways have the potential to be protective barriers in the event of large wildfires. Eighteen agencies and a multitude of landowners and experts collaborated to prioritize wildfire mitigation areas and actions. “Collaboration is essential to invasive species management in Hawaiʻi, enabling organizations to pool resources and achieve landscape-scale goals. It is also the only practical approach to managing wildfire-prone vegetation,” said Radford.

Dry fountain grass lining a road in Hawaiʻi.

“The challenge of managing invasive species in Hawaiʻi is complex. As an archipelago, we mostly rely on importing the goods we need, yet don’t necessarily have the right environmental regulations for such a unique ecosystem or enough resources to inspect and make sure imported goods are not invasive or that pests aren’t hitching a ride on all these goods,” remarked Frohlich. “It’s really a multi-pronged approach to manage invasive species—communicating and educating residents and stakeholders about the risks and how they can be a part of the solution, while also continuously monitoring and controlling outbreaks, and then building on those successes.”

Prevention

Prevention is our best defense. The most effective way to manage invasive species is to stop them from entering the ecosystem and establishing themselves in the first place. This involves setting up policies and practices to block their entry, such as trade regulations, biosecurity measures, and public education efforts to inform people about the risks invasive species pose.

Early Detection and Rapid Response

Identifying invasive species early and taking swift action is essential to prevent them from spreading. This process involves consistent monitoring and surveillance to spot any new arrivals, followed by quick measures to either eradicate or contain the species before it becomes a larger problem.

Radford added, “Much of our early detection work takes place along roadsides as part of our team’s projects. Many invasive species are unintentionally—or sometimes intentionally—spread by people, and roadways often serve as major dispersal corridors. As a result, surveying roadsides and other pathways of movement across the islands is a critical component of effectively managing invasive species in Hawaiʻi.”

Control and Management

Once invasive species are established, a wide variety of control methods are used to manage the spread and reduce impacts to the ecosystems of Hawaiʻi. These can include the physical removal of invasive species, targeted chemical treatments, biological control using natural predators, and habitat restoration efforts to support native species. For each invasive species, there are best management practices for removing that species to make sure it doesn’t spread from the place where it was found. Tapping into networks like the Hawaiʻi Ant Lab and the island invasive species committees (ISCs) helps SWCA provide the latest practices for clients.

“While we prioritize control and management efforts based on several factors—such as proximity to known infestations, the value of the area, and the level of risk to nearby infrastructure—we also recognize that invasive species management is a statewide effort with numerous initiatives happening across Hawaiʻi,” said Radford. “At SWCA, through our client projects and connections from our years of experience, we have the pulse of all these different efforts and can advise on investing in complementary efforts—and that helps save clients time and money while still making an impact.”

Restoration, Revegetation, and Research & Development

Restoring areas affected by invasive species is essential to the recovery of biodiversity and ecosystem functions. This often involves replanting native species, improving habitat conditions, and removing invasive species to allow native flora and fauna to thrive.

Frohlich mentioned, “Depending on the needs of the client, we have the capabilities to take on restoration and revegetation activities. We’ve also created resources to empower others on the restoration and revegetation aspect, including a booklet on Hawaiian native plant recommendations according to ecozone, which provides information on which Hawaiian native plants are suited to various environments across the islands. We’ve developed pamphlets on where to source these native plants in Hawaiʻi and provided trainings on how to properly maintain native plant species.”

Ongoing research is critical to understanding the biology and ecology of invasive species, as well as developing new management techniques. This could look like connecting clients to researchers and testing creative, cost-effective solutions, such as using domestic sheep as a novel and non-chemical method for controlling invasive plants.

Education and Outreach

Engaging the public and stakeholders through education and outreach is vital for successful invasive species management. This involves raising awareness about the threats of invasive species, promoting best practices for prevention and control, and encouraging community members to become involved in management efforts. There are many ways community members can help, including submitting a report of new pest sightings at 643pest.org or volunteering for an invasive species committee event, such as the ones that the O‘ahu Invasive Species Committee organizes.

Danielle Frohlich, lead botanist for the Pacific Islands at SWCA, mapping plant species for protection or removal near Waimea Canyon

Invasive species management in Hawaiʻi is a complex and ongoing challenge that requires proactive and strategic approaches. As SWCA’s invasive species experts continue to lead these efforts, the importance of timely interventions cannot be overstated. The longer invasive species are left unchecked, the greater the financial and ecological costs will be. Small investments in prevention and control can avert costly future interventions.

SWCA’s Pacific Islands team has a wealth of local expertise, with many colleagues coming from land management backgrounds working with the ISCs, watershed partnerships, and The Nature Conservancy. This level of experience ensures that we deliver effective strategies tailored to Hawai’i’s unique environmental challenges and cultural context. By leveraging collective expertise and fostering collaboration, SWCA and our clients play a pivotal role in preserving Hawaiʻi’s ecosystems and safeguarding a sustainable future for the islands.

For more information about invasive species management in Hawaiʻi, please contact Danielle Frohlich or Adam Radford.