2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

What a Dog's Nose Knows

Dogs can smell up to 100,000 times better than humans, making them powerful tools in environmental work by detecting things like underground oil since the 1990s.

Brent joined SWCA in 2020 and manages the company’s digital external content including SWCA.com, The Wire e-newsletter, and social media channels (Instagram, LinkedIn, YouTube, Facebook).

Brent graduated from the University of Georgia with a B.A. in Political Science. He lives in Madison, WI where he is learning to love the snow, and enjoys watching Formula 1 racing, trying new recipes, and working on a never-ending list of DIY projects.

Allison is a staff biologist in SWCA’s Arlington, Texas office. She works with Moxie, a springer spaniel who sniffs out bird and bat fatalities on wind farms.

Allison and Moxie on site at an SWCA client’s wind farm.

Imagine having a coworker who is innately talented at a particular task, finishes in a fraction of the time it would take you, and does it all with an unwavering determination and endless enthusiasm. That’s Moxie, a 3-year-old springer spaniel who sniffs out bird and bat fatalities on wind farms. Moxie loves her job and she’s very good at it.

A dog’s sense of smell is estimated to be 10,000 to 100,000 times better than a human’s, meaning a dog’s nose knows better how to find by smell what human eyes often miss. Since the 1990s, dogs have been making their way into environmental field work, detecting things like underground oil contamination, and endangered and invasive species of plants and animals.

Human-led field surveys for particular species can be tedious and expensive, sometimes coming up empty-handed altogether. With their powerful noses able to locate odors over large distances, dogs are much better suited to locating species in difficult survey conditions. Allison Locatell, a staff biologist in SWCA’s Arlington, Texas office, was convinced there was a way around our natural limitations.

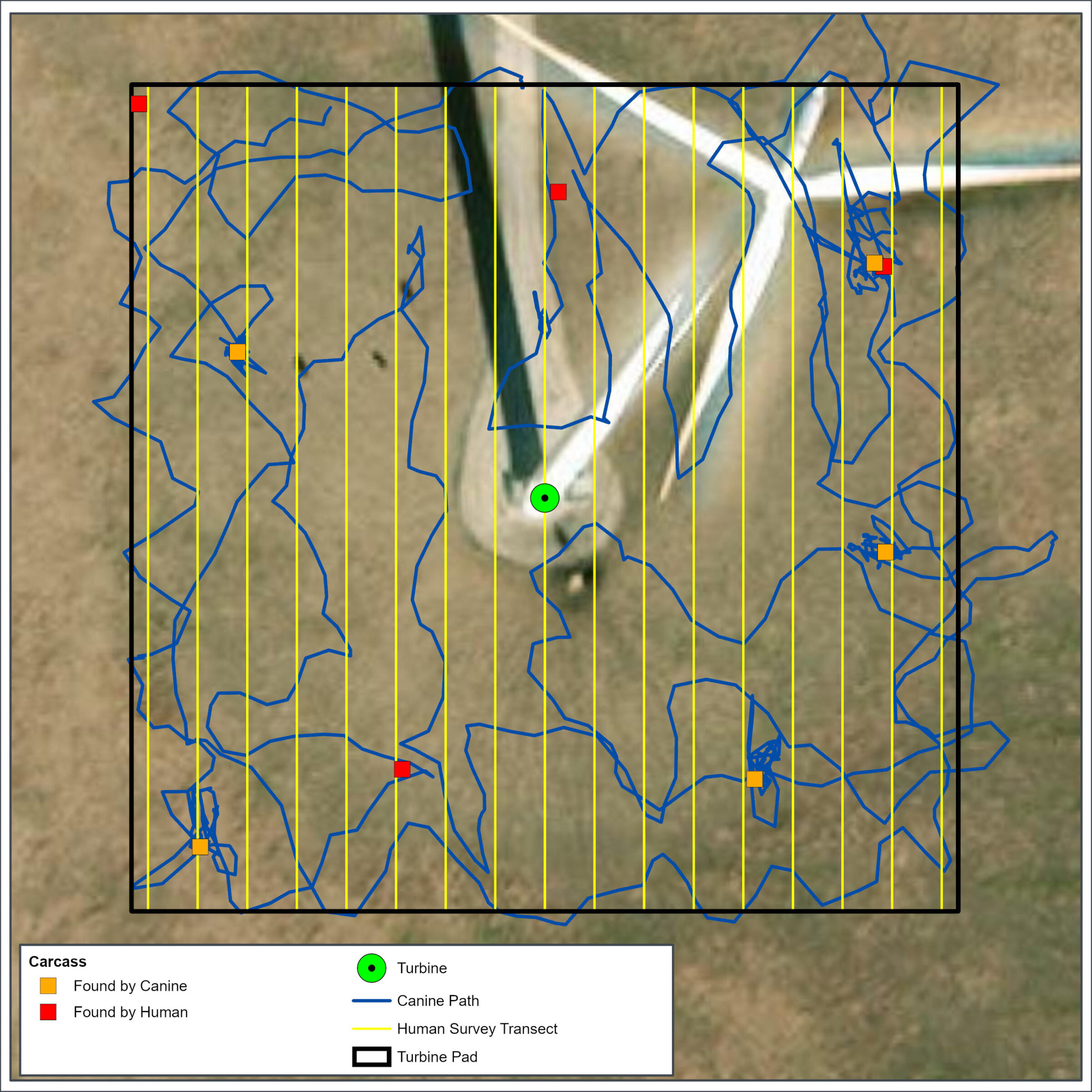

Moxie wears a GPS collar to record her search path at each turbine, allowing Allison to monitor survey coverage in real-time.

“As the surveyor, I was supposed to visually find fatalities as small as a mouse in a field of chest-high vegetation where I couldn’t even see my own feet,” Allison said. ”Knowing there was a better solution and wanting the best results for our clients, I asked others at SWCA about using dogs. When I was given the go-ahead to investigate it further, I ran with it.”

Goggles protect Moxie’s eyes from irritants and impacts when moving quickly through dense vegetation. Play time with a sheepskin toy is her reward after each find.

“This was a great example of a creative solution we strive to find for our clients,” said Josh Perry, Director of SWCA’s Arlington office, about Allison’s suggestion to use dogs in field studies. “Taking on a project like this speaks volumes to the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit of so many of SWCA’s technical staff.”

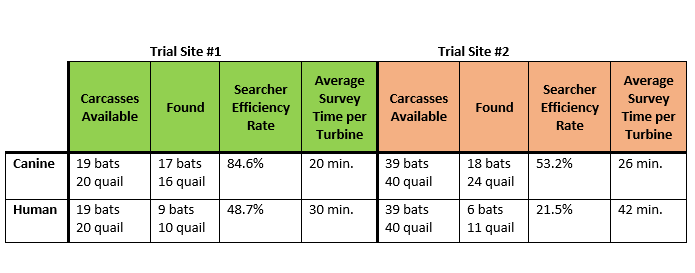

The trials were held within a single season in three vegetation levels commonly found on wind farms. Trial Site #1 had bare ground agricultural fields, and Trial Site #2 had medium coverage (ankle height vegetation) and difficult coverage (knee height). Surveys for bat and quail carcasses compared the canine-handler team and a human surveyor on the same days, each searching for the same sample carcasses. To avoid the possibility of scent contamination, another SWCA teammate walked to randomly generated points within each turbine plot and tossed the carcass 10-15 feet. Each turbine was searched by the canine-handler team first, then by the human so the canine would not follow a teammate’s scent to each carcass.

The canine-handler team performed 73% better than the human surveyor on Site #1 and 147% better on Site #2 with more difficult vegetation cover. Not only did the canine-handler team find more carcasses, but they also finished an average of 10-16 minutes faster per turbine.

Since the trials were performed on active wind farms, finding real-world bird and bat fatalities was a known possibility. Both survey teams found incidental fatalities in addition to the sample carcasses. However, the most challenging and impressive of these finds were made only by Moxie, who was able to find a fatality that was almost completely buried by a previous ant infestation as well as a piece of bat wing and tuft of fur smaller than a pinky finger.

Moxie’s most difficult finds included a previously buried bird carcass and small pieces of bat wing.

Searching by smell rather than sight alone allows Moxie (blue) to cover the same area more quickly than the human surveyor’s transect paths (yellow) evenly spaced across the survey plot. Moxie completed this search 20 minutes faster than the human surveyor.

“SWCA has been using canine-searcher teams very effectively on our projects in Hawaii, where they are up to six times more efficient than humans alone in difficult-to-search volcanic environments,” said Ann Widmer, an ecologist in SWCA’s Denver office.

After a long day of searching, Moxie relaxes with a belly rub and one of her favorite toys.

“However, SWCA hasn’t had this capability in the mainland U.S. until now. Many of our wind energy clients are interested in preserving existing land uses beneath the turbines, but it is sometimes necessary to mow the vegetation grown for crops or grown to support livestock in order to make the area searchable by humans. With a well-trained dog on the team, mowing may not be necessary. Likewise, many of our clients are required to monitor large areas for eagle fatalities. Dogs are perfect for this task—covering more area in less time and locating targets with an exceptionally high degree of precision. We’re continually identifying new applications where dogs may be a real asset.”

Elsewhere in the U.S., dogs have been used to find Oregon silverspot butterfly larvae that are smaller than a grain of rice and haven’t been detected in the last 40 years of human-conducted surveys. They have also recently been used to find floating scat samples (which only float for a short period of time) of declining Southern resident orca whale populations by sniffing from the bow of a boat.

Detection dogs are already making a difference in environmental research and conservation in amazing and unexpected ways. With support from SWCA, Allison is planning additional canine studies, using sound science to find creative solutions to better protect threatened and endangered species, eradicate invasive species, and mitigate negative impacts to clients’ projects and bottom line.

Video: Moxie and Allison in Action!

Read more from The Wire, Vol. 22, No. 1 below: