2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

Ephemeral but Not Forgotten: SWCA Works to Protect Playas on the Ogallala Aquifer

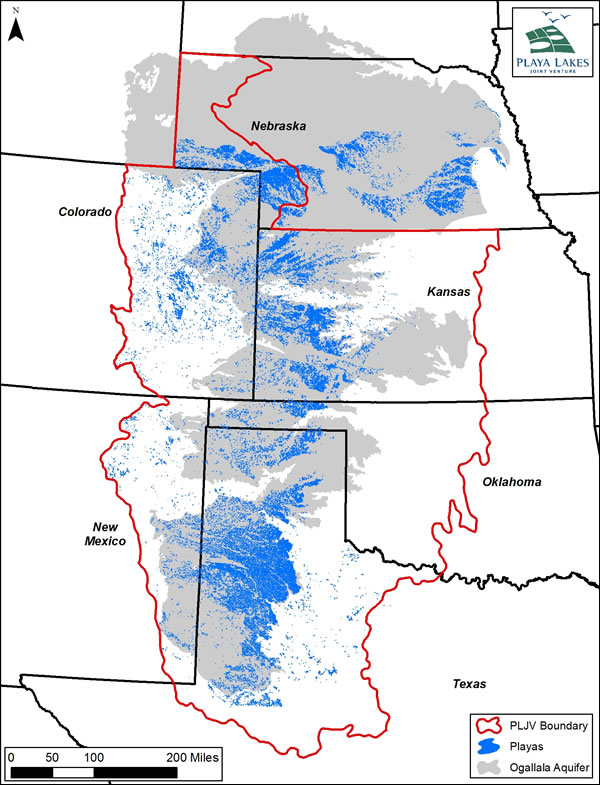

Scattered across the western Great Plains exist an unprotected, yet vital geological feature: playas.

Map of the Ogallala Aquifer and its playas. Image provided by Playa Lakes Joint Venture (PLJV).

Scattered across the western Great Plains exist an unprotected, yet vital geological feature: playas.

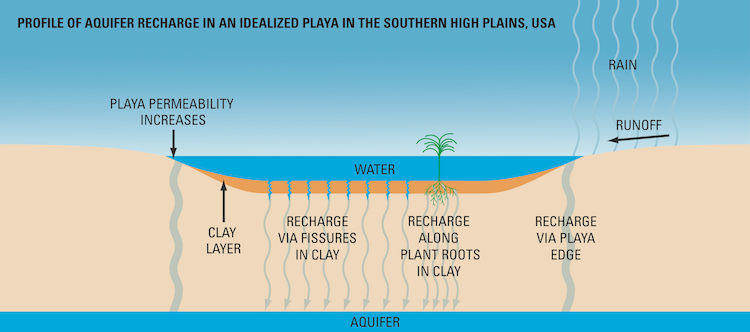

Unfortunately, these playas are under threat from sedimentation from surrounding croplands. Soil runoff from the croplands affects the playas’ natural hydrology and size. The sediment accumulation reduces the playas’ potential water capacity, causing an increased rate of evaporation and limiting the ability of the water to drain into the aquifer below.

As the Great Plains region increasingly struggles with drought and declining aquifers, the protection of these playas is paramount to the survival of the region and its inhabitants.

“It has been widely recognized that these playas are critical for wildlife at local and landscape levels, but they are also crucial for clean water for the region,” said Willow Malone, biologist in SWCA’s Denver office. “We recognize that land management and working with landowners and energy developers is key to protecting these playas.”

Profile of how an aquifer recharges. Image provided by Playa Lakes Joint Venture (PLJV).

An inundated playa near a wind turbine in Kansas.

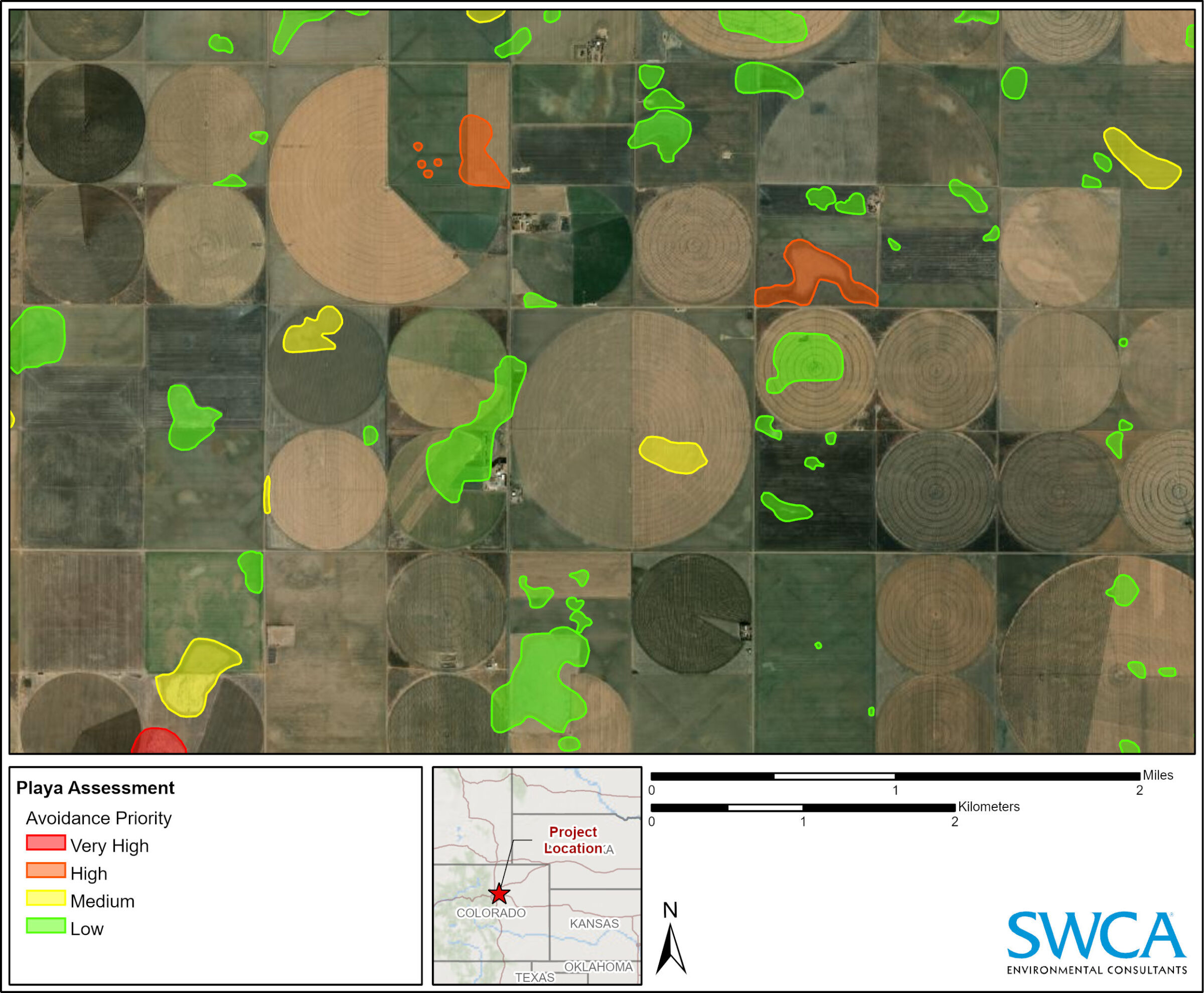

Luckily, there has been a concerted effort by landowners, conservation groups, and energy companies to take a proactive approach towards mitigating impacts. To assist with protection efforts, Malone, along with a large, companywide team at SWCA, worked to develop a standardized assessment method and prioritization standards for playas to create a GIS “hotspot map”. The hotspot map prioritizes individual and clusters of playas based on their current ecological quality to target the playas most in need of avoidance of developmental impacts and conservation.

“Our clients actively strive to avoid these playa clusters,” Malone said. “This map helps them in these efforts.”

SWCA’s team developed this standardized hotspot model with the help of Playa Lakes Joint Venture’s (PLJV) most recent Probable Playa Version 5 dataset, peer-reviewed literature, and the PLJV playa quality standards.

Snapshot of playa locations and avoidance priority status as assessed by SWCA for an undisclosed location

Eight criteria were considered for the avoidance ranking model: dominant land cover, playa size, playa connectivity, health status of the playa, oil and gas infrastructure presence, evidence of farming, presence of hydrological modifications, and road and railroad presence.

The hotspot map encourages developers to coordinate with landowners, federal and state agencies, and wildlife conservation groups to update the project layout and avoid sensitive areas. These local conservation efforts cascade to the landscape level, benefitting the industry, wildlife, and public on a large scale.

With the creation of this GIS ranking model, SWCA is assisting developers in protecting unique and critical habitats throughout the Great Plains.

Read more from The Wire, Vol. 22, No. 1 below: