2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

Seeing Eye to Eye: How Visual Resources Build Consensus on Sustainable Development

Our landscape is a finite resource, rich with aesthetic features. These are not simply the rivulets forming a stream of water, an old-growth stretch of forest, or a span of agricultural soil, but also the entire landscape character of the view itself.

Since joining SWCA in 2022, Sarah has mainly led external communications, including content strategies, narratives, and the development of SWCA’s award-winning publication, The Wire. As a strategic communicator, Sarah finds the best part of her role is connecting with the incredibly intelligent and talented people across the company to help tell their story to prospective clients and the broader world, whether that’s through expert insights or earned media.

With a journalism degree and nearly 15 years of marketing communications experience in the A/E/C industry, Sarah is particularly passionate about storytelling to amplify the brand and drive results. Outside of work, Sarah enjoys spending as much time as possible in the great outdoors with her family and friends.

Our landscape is a finite resource, rich with aesthetic features. These are not simply the rivulets forming a stream of water, an old-growth stretch of forest, or a span of agricultural soil, but also the entire landscape character of the view itself. You can observe such features and landscapes when driving across the plains in the Midwest, winding through the mountains of the West, or peering out into the ocean along the East and West coasts.

Genius loci, a Latin term that refers to one’s sense of place, is often used to describe our personal connection to landscapes that we feel are significant and have impacted our lives. So, it’s not surprising when people are hesitant to see changes in the landscapes they are connected to, even when the change directly benefits society.

We recently met with Visual Resources Director Chris Bockey and Lead Landscape Designer Cullen Chapman to learn more about the growing demand for visual resources expertise.

“Communities can proactively identify and understand the landscapes and views that should be protected in the future by asking: What views are important to the people who live here? Where do we want to develop and where do we not want to develop?”

Bockey: Visual resources are what we see and value in our surrounding landscapes. The colors, textures, terrain, geological and hydrologic features, vegetative patterns, and built infrastructure all constitute visual resources. These elements influence the aesthetic appeal of a landscape — and when these elements change, it changes the value of that landscape.

Visual resources are becoming an ever-increasing point of interest for the public when it comes to large infrastructure projects. People are interested in understanding what may be developed in their backyard, so to speak, and voicing their opinion when it impacts their landscape or view. Even the boom in tourism to our public lands and natural landscapes can be considered one of the thriving industries driving the demand for proactive visual resources planning and management.

We can all see the huge push for renewable energy right now: utility-scale solar developments, onshore and offshore wind farms, and the need for new generation facilities and transmission lines. All these developments have the potential to change what we see and value in the landscape, which is where visual resources expertise helps to analyze and mitigate visual impacts.

Bockey: Regulatory requirements certainly play a role. On a federal level, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) is the basis for much of the visual resources work we do. If there is a federal action that may impact visual resources, the impacts must be assessed as part of the NEPA process. Some federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), have policies or guidance related to the inventory and assessment of visual resources. Additionally, many state and local governments and municipalities have policies or guidance related to visual resources: for example, the California Environmental Quality Act.

Disclosing what a project is and what a project looks like to the community, even though the developer may not need to go to that level of effort, is a great way to build community relationships.

That said, I’ve worked on several projects where specific policy or guidance related to visual resources was not in place, but local municipalities or project proponents will do their due diligence because it is in the best interest of the project to have stakeholder and public engagement. Disclosing what a project is and what a project looks like to the community, even though the developer may not need to go to that level of effort, is a great way to build community relationships.

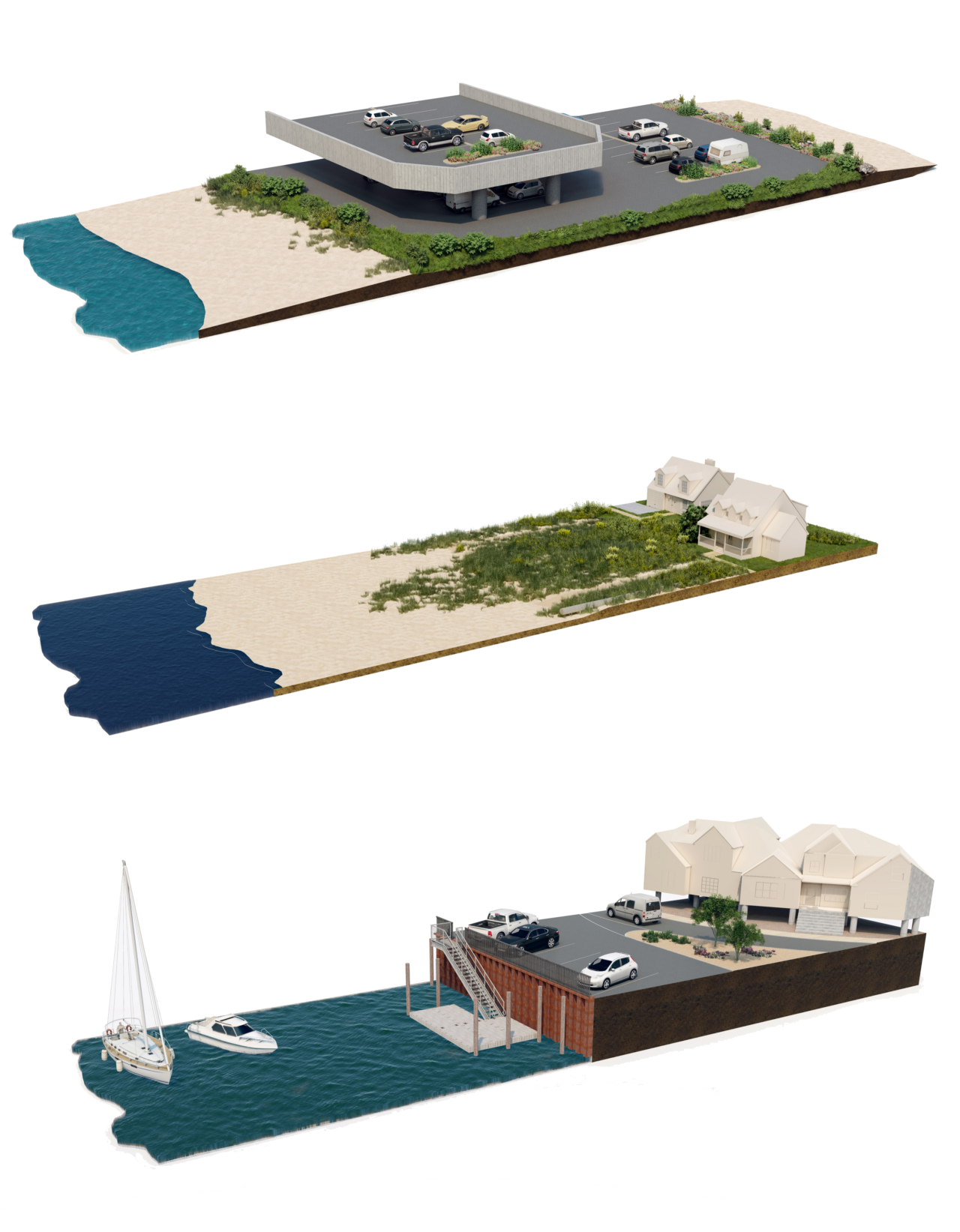

Chapman: Visual resources are frequently the face of a proposed project for the public. People often have a preconceived perception of what a project may look like in their community before they see what it will actually look like. Our role, as visual resources experts, is to accurately portray what a new transmission line, wind farm, solar project, or various other projects will look like in the landscape when constructed. We have a responsibility to represent these projects exactly as they are intended to be developed, without bias.

Visual simulations and analyses paired with strategic communication can be critical in helping decision-makers, interested stakeholders, and the public understand potential impacts to their community and build consensus.

Bockey: Often as part of a visual resources analysis and the visual simulation process, we are asked to be expert witnesses and provide pre-file, written, and in-person testimony as part of the permitting process. The potential to be an expert witness and provide testimony guides our overall methodology; the accuracy of the analyses being provided is of utmost importance.

Before-and-after visual simulations are effective stakeholder and public communication tools because they convey real visual impacts – from numerous viewpoints – on a landscape through accurate representations of scale, location, color, and texture.

Bockey: Energy generation and transmission, mining, and government agencies all have projects that aim to balance economic and social goals with environmental protection and cultural preservation. Visual resources analysis and an understanding of basic design principles can help projects move forward in the permitting process by informing decisions and providing recommendations about design, potential mitigation, and implementation.

With accurate visual simulations in hand, visual resources experts can help project proponents potentially reduce the visual impact of a project by considering mitigation measures. Mitigation may focus on the design elements, such as choosing a paint color to blend more with the landscape or using natural vegetative screening, earth berming, and fencing. For large-scale projects, we provide recommendations on topics such as micro-siting wind turbines, solar farm layouts, and associated transmission. For example, if it’s feasible, we may suggest relocating the alignment of a transmission line to the backside of a ridge where it’s less visible.

Visual analysts consider impacts to a landscape and humans beyond infrastructure, for example, the reach of sunlight flickers from rotating wind turbines.

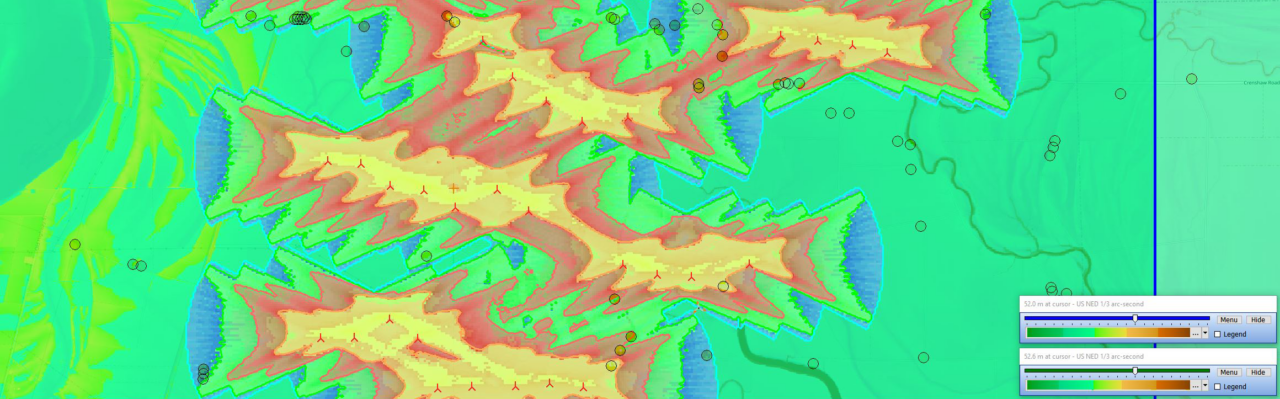

Bockey: Visual resources experts tap into a plethora of tools and approaches to fit the needs of the client and project, which can include baseline inventories, viewshed analysis, visual simulations, visual impact assessments, recommended mitigation (if appropriate), and other specific analyses for solar and wind development projects, such as glint or glare and shadow flicker.

A key element of the analyses includes translating what we see into words that describe the existing setting and immediately creating that picture in someone’s mind of what this landscape looks like. That may not sound complicated, but there’s an art and science to it.

On the analysis side, the two main reports are a visual impact analysis and a visual resources assessment; both are geared to satisfy national, state, and local regulations. The goal of a visual impact analysis is to understand the impacts of a proposed development early in the planning process and adjust the design to minimize negative effects and create more compatibility with the landscape. A visual resources assessment identifies and characterizes the visual quality of a specific geographic area, typically carried out as part of an environmental impact assessment or land use planning process related to a proposed project.

Chapman: A key part of visual resources, visual simulations are intended to clearly communicate an accurate representation of what a project will look like in the landscape. Often, static simulations, which are essentially static images to convey the existing condition and proposed project condition, are one of the best options because of their simplicity. Additional options include dynamic simulations, day-to-night simulations, fly-through simulations, and simulations using 360-degree, virtual, or augmented reality.

Simulated visualization of transmission line construction.

Visual resources experts partner closely with the geographic information system (GIS) and data acquisition teams who provide the geo-specific topographic and environmental data that become the groundwork for our workflow. Our role is to assess the needs of the project and what the client needs to convey to their audience. Accuracy and comprehension are a top priority in determining which of the many exciting visual technology and respective formats we can provide.

Bockey: I see water as the next big element we’ll focus on when it comes to visual resources, particularly around water bodies, like reservoirs and changes in water levels. We’re already having conversations about the visual impacts of building a new reservoir or changes to an existing reservoir because of a new dam being built.

I also see the potential of more communities using visual resources long before any type of development is happening, like a visual resources inventory to set a baseline. Communities proactively identify and understand the landscapes and views that should be protected in the future by asking: What views are important to the people who live here? Where do we want to develop and where do we not want to develop?

Chapman: Building on that idea further, I could see a stronger need for visual resources expertise to be applied to protect our landscapes from a changing climate. As we define new resiliency strategies, whether that’s coastal restoration, wildfire planning, or water resources protection, there is an opportunity to visualize these approaches and project implementation. We can create accurate visualizations of those strategies to convey and communicate to the public what they will look like when complete.

An SWCA technician captures photos for the visual impact analysis of a proposed transmission line in Nevada.

Bockey: We live in a visual world; one that will continue to change and evolve. I like to say that we try to be a mix of Bob Ross and Ansel Adams with how we convey the visual landscape with words and visual simulations. I’m personally excited to keep growing our SWCA visual resources team, to keep using visual resources as a key tool for moving sustainable development projects forward, and to keep challenging ourselves with new technologies and approaches to meet the ever-changing needs of our world.

To learn more about visual resources services at SWCA, please contact Chris Bockey.

Chris Bockey

Growing up in Colorado and spending formative years in the mountains, Bockey gained an appreciation for the landscape early in life. A degree in landscape architecture led to environmental planning, which led to playing a key role in how landscapes are shaped. Bockey has more than a decade of experience as an environmental planning and visual resources specialist. His areas of expertise include the inventory and analysis of visual and historic resources and the analysis of public and private land resource impacts associated with multiscale infrastructure projects.

Growing up in Colorado and spending formative years in the mountains, Bockey gained an appreciation for the landscape early in life. A degree in landscape architecture led to environmental planning, which led to playing a key role in how landscapes are shaped. Bockey has more than a decade of experience as an environmental planning and visual resources specialist. His areas of expertise include the inventory and analysis of visual and historic resources and the analysis of public and private land resource impacts associated with multiscale infrastructure projects.

Cullen Chapman

A natural observer since childhood, Chapman always had an artistic side and enjoyed spending time in Japanese gardens thinking about how form, shape, and materials made you feel in a space. This led to the study of landscape architecture and studying the psychology, historical relevance, context, and other elements of place that lend themselves well to visual resources. With 10 years of experience as a landscape designer, Chapman focuses on graphic visualization, coordinating visualization and design efforts ranging from static simulations to 3-D animation to virtual reality.