2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

SWCA Expands Horizons: from the Grand Canyon to the Great Lakes

From an early age, Dr. Steven Carothers’ interest in the Grand Canyon led to a lifetime of preserving the ecology of this natural wonder.

Quinn has been a member of SWCA’s Marketing Team since 2019. As a content developer, she loves learning about SWCA’s people, projects, and services through writing articles. Quinn also teams with departments across the company, managing and developing internal communications.

A proud Spartan, she graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in Sustainability and Environmental Journalism. Born and raised in Michigan, Quinn moved to Denver to join SWCA (and enjoy all the mountain activities).

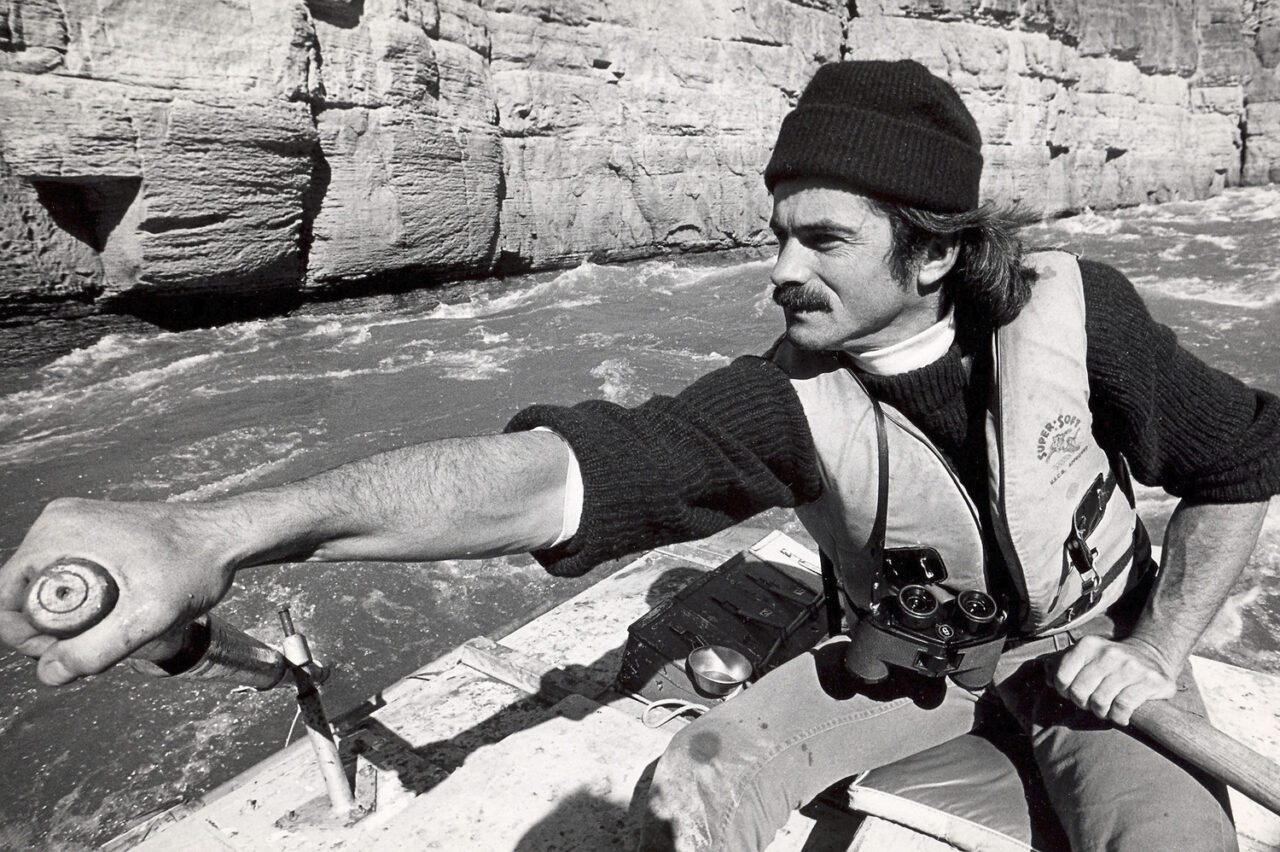

It is often said that the Grand Canyon is the birthplace of SWCA. From an early age, Dr. Steven Carothers’ interest in the Grand Canyon led to a lifetime of preserving the ecology of this natural wonder.

“I was first introduced to the Grand Canyon at 3 years old, attached by a rope to my father on the canyon’s Bright Angel Trail. My mom and dad were infatuated with the Grand Canyon, and they passed that on to me,” said Carothers, SWCA’s founder.

Grand Canyon Bright Angel Trail – SierraDescents

Encapsulating millions of years of geological processes, rare ecological diversity, and significant cultural heritage, the Grand Canyon is a natural marvel. Though ubiquitously beloved for its spectacular views and recreational draws, the environmental challenges that face the park are far less acknowledged.

Carothers first started tackling these challenges in the Grand Canyon in the 1970s. He developed management systems for backcountry and river use to minimize human impacts, performed monitoring studies that supported the preservation of native fish populations, and evaluated the damaging impact of feral burrows on the park ecology. Hundreds of projects and over half a century of research later, his work has shaped our understanding of the Colorado River ecosystem and influenced the park’s resource management practices. These early projects also laid the groundwork for what became SWCA — Steven W. Carothers and Associates.

Steven Carothers Working in the Grand Canyon, Late 1970s

After establishing a strong foundation throughout the West, SWCA has continued to grow its presence across the U.S. and beyond. Entrenched in Carothers’ passion to bring sound science and creative solutions to pressing ecological issues facing the Grand Canyon, SWCA now sets its sights on restoring another one of America’s most expansive and treasured landscapes — the Great Lakes.

Just as Carothers’ love for the land planted SWCA’s roots in the Southwest, amplifying efforts in protecting the Great Lakes is more than just a business case for SWCA’s President and CEO, Joseph J. Fluder, III.

“Growing up in Chicago with Lake Michigan as a backdrop and visiting my grandparents’ forested property in southwest Michigan, it was always a magical experience being near such an immense lake and its surrounding rivers. It is where my love for geography, geology, and water resources developed at a young age. My appreciation for the impact and the power of the Great Lakes has only grown,” Fluder said. “It is extremely meaningful to me that SWCA is playing a role in the restoration and recovery of this region.”

As the largest system of fresh surface water in the world, the Great Lakes — Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario — and the surrounding area are in critical need of collaborative protection.

“Celebrating the 10th anniversary of our Chicago office this year has given us a great opportunity to reflect on how far we’ve come in the Midwest while we look forward to what’s next,” said Sarah Zink, SWCA’s office director for Chicago. “Our seasoned Midwest experts, combined with a strong network of local connections and partnerships are driving our growth. And while I’m proud to lead our team in Chicago, we could not be successful without our people across the Midwest, from Minnesota to Pennsylvania and New York.”

Over the past decade, SWCA specialists in wetlands, cultural resources, habitat restoration, and permitting have been guiding clients through every stage of complex environmental challenges in the Great Lakes. The addition of more ecological restoration and climate-driven expertise in recent years further broadened SWCA’s support for the Great Lakes’ protection through a healthy and thriving watershed.

Lake Michigan coastline, Chicago, Illinois

“We are already seeing how climate change is causing significant impacts to this region, and there are many communities that will be (and have been) disproportionately impacted by its effects,” said Zink, who grew up in the Chicagoland area and has focused much of her career on invasive species management and restoration in the Great Lakes. “Conservation and habitat preservation are also pressing environmental concerns. For example, in Illinois, less than 0.01% of the original 21 million acres of tallgrass prairie remain.”

It is hard to appreciate the sheer vastness of the Great Lakes until standing on the shoreline of Lake Michigan, unable to see the other side, and thinking, what ocean is off the coast of Wisconsin?

Lake Michigan off Wind Point, Wisconsin

Accounting for one-fifth of the world’s freshwater, spanning 11,000 miles of coastline, and supplying drinking water to more than 40 million U.S. and Canadian residents, the Great Lakes are aptly named. These massive bodies of freshwater provide far more than drinking water. Immense recreational value, pivotal transportation routes, and expansive and rare biodiversity are all celebrated and invaluable aspects of the Great Lakes.

Importance notwithstanding, monumental environmental challenges threaten the Great Lakes today. Many of these parallel the topics SWCA has been tackling in the Grand Canyon over the past 40 years: water quality, invasive species management, land development impacts, legacy industrial contamination, wetland and habitat degradation, threatened species, and coastal resiliency, to name a few.

“The cultural, ecological, and economic significance of the Great Lakes and its surrounding region is immense. As SWCA extends our proven environmental services into this region, we embrace the responsibility of aiding in its preservation,” said Eric Myers, client services director at SWCA.

It is an exciting time for ecological restoration in the Great Lakes. Now more than ever, stakeholders are drawing up plans and projects to restore the rich tapestry of critical ecosystems in and around the lakes — aquatic, forested, marsh, wetland — for the more than 3,500 species of plants and animals that dwell in them.

Following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 and other legislation, the federal government is prioritizing science-driven programs, which is spurring a renewal in funding and focus for completing these large-scale restoration projects. With project road maps already in place, the Great Lakes are in a phenomenal position to receive this funding, and SWCA is well-equipped with the resources and regional expertise to help see these projects through.

In one such example, SWCA is assisting with the removal of a dam on Michigan’s Kalamazoo River, one of 14 large-scale federally funded projects to restore the river. SWCA will perform bank restoration, habitat creation, native planting, and ecological monitoring for the next couple of years to restore the river to its natural state.

Kalamazoo River, Michigan

“Our commitment to do good science, our eagerness to be a good partner, and our distinct understanding of the regulatory drivers and issues facing the region makes SWCA uniquely qualified to address these environmental challenges in the Great Lakes,” said Tony St. Aubin, ecological restoration director at SWCA. “We work with a wide variety of partners on ecological restoration projects, listen to the concerns, and develop nature-based solutions that help meet the needs of all stakeholders, now or in the future.”

St. Aubin grew up in Michigan and is an avid recreator on the waters of the Great Lakes — fishing, boating, and surfing (yes, even surfing). He has also spent the bulk of his 25-year career focused on ecological restoration in and around the Great Lakes area. It is safe to say that St. Aubin has a personal investment in restoring these areas.

“When you’re able to successfully remediate these areas, there’s a real social return. There’s reinvestment in these communities that often have been overlooked for a long time,” St. Aubin said. “Take Boardman River in northern Michigan, for instance. It’s categorized as a blue-ribbon trout stream. It had four dams, one of them a defunct hydroelectric dam that became a real liability. I was on the team that helped remove it and restore the riverbank. We installed approximately 500 large woody habitat structures and completed a whole lot of bank restoration. And now, it’s a phenomenal place to visit. My family and I have spent many a Saturday floating down that river; my kids have caught trout out of that river. And that’s the return to this, right? That’s what it’s about. Being able to restore these habitats so people can use them, make memories, and feel safe to enjoy them.”

The demand for a clean energy transition, the emergence of new and better energy technologies, and the rise of federal funding is the power trio accelerating renewable energy developments across the country. With the zeal (and funding) to advance renewable energy in the Midwest comes the need to ensure that these projects are fully vetted and environmentally sound.

In addition to addressing landowner opposition and responding to public concerns, developers must continue to navigate ever-tightening and continually changing state-level permitting and regulatory requirements, including those for wetlands, water resources, and natural resources.

Sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera)

“The landscape for renewable energy is particularly challenging in the Great Lakes area. Being so close to these enormous bodies of water means there are wetlands to consider across the adjacent states that limit where these developments can be placed,” said Hailey Preston, a renewable energy project manager, natural resources team lead, and wetland scientist at SWCA.

“Bats are also paramount right now; they fulfill essential roles in the ecosystem but several species in the area are on a steep decline.”

Because of this, complications accompany the development of any new renewable energy sites, and conversations about offshore wind and other experimental renewable energy developments in the Great Lakes are particularly hot topics.

“Our ability to provide a wide range of regional expertise, to be nimble and flexible, as well as to lean on our sound science and creative solutions approach when tackling complex projects is crucial to navigating clients through the renewable energy development process,” Preston said. “Our clients trust us to do high quality work every step of the way, from feasibility assessments, wetland delineations, and bat surveys, to construction compliance and post-construction monitoring.”

Wind Turbines, Illinois

Growing up in rural Michigan, Preston loved the outdoors and realized her passion for wetlands and water — constants in Michigan — could be her career focus. With a deep understanding of the unique constraints of the landscape, Preston and her peers work with clients to ensure the success of renewable energy projects around the Midwest.

“Tried and true, accurate, and scientifically sound services go a long way,” Preston said. “We live here. We care about our clients, we care about the work, and we care about making a positive impact in the Great Lakes with these projects.”

Renewable energy and electrical transmission lines are not the only infrastructure developments driving cultural resources management in the Great Lakes. When looking at the entire region, there is a considerable need to update and replace aging infrastructure, particularly roadways and bridges.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the states surrounding the Great Lakes all received a C or C- on their latest infrastructure report cards. These transportation upgrades all require proper cultural resources compliance and permitting to continue.

The interconnectivity of the Great Lakes states adds a layer of complexity. Projects that cross multiple states or jurisdictions face different regulatory requirements.

“We always want to focus on our clients, understanding their needs and challenges. And part of that is being keenly aware of how regulations and funding opportunities differ state by state,” said Dr. Brandon Gabler, SWCA’s strategic growth director of the Great Lakes and Midwest region. “When a project has different regulatory requirements across states, that’s where we can provide environmental solutions that seamlessly integrate those needs.”

Lake Erie

Gabler started his archaeology career near Lake Erie and is well-versed in the unique cultural aspects of the Great Lakes area. For instance, archaeologists in this region need to have specific knowledge of the landscape to perform surveys at old logging and mining sites that are distinctive to the upper Midwest. Additionally, the rich, productive forests in the Great Lakes region present their own challenges for surveying when archaeological deposits are likely to be far beneath the surface.

“It’s also easy for us to connect our cultural and natural resources capabilities. For example, if our ecological restoration experts are working on an erosion control project along the shores of one of the Great Lakes, we can bring the right colleagues to assess the damage to archaeological deposits that are now underwater due to changing water levels of the lakes,” Gabler said. “SWCA has the technical expertise and local knowledge needed, backed with the resources of a nationwide firm, to be a great partner to our clients in the Great Lakes region and beyond.”

Whether it is supporting federal programs to monitor zebra mussels, working with developers to minimize damage to dwindling wetlands, partnering with groups to restore areas plagued by legacy contamination, or monitoring sites to preserve precious natural and cultural resources, SWCA is equipped with the experience and regional knowledge to tackle these unique challenges.

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Michigan

In the spirit of its start in the Grand Canyon, SWCA continues to lead with scientific integrity, creative problem solving, and dedicated expertise while scaling up to protect the Great Lakes region.

“Dr. Steven Carothers set the bar high, but SWCA is up to the challenge. We’ve already established a strong base in the Great Lakes, but in a lot of ways, we’re just beginning,” Fluder said. “Our goal is not solely focused on growth. It’s about cultivating a positive impact through lasting partnerships and meaningful projects. It’s about creating value for our people, our clients, and our communities.”