In April 2016, the University of Utah began renovating the George Thomas building, one of eight historic structures that sits in the campus’ u-shaped President’s Circle, to become the Crocker Science Center. Soon after construction started, however, the unearthing of human skeletal remains quickly halted the project.

An analysis of the remains by the state determined that they were anatomical specimen, cadaver bones that could be associated with the University’s first medical school. The archaeological excavation, led by SWCA, uncovered other skeletal remains, bone fragments, and artifacts dating back to the early 1900s.

Through extensive historic research, archaeological investigation, and analysis of the remains, SWCA worked closely with university and state officials to determine the story of the bones and why they were initially disposed. The prevailing theory was that the cadavers had been donated from a local prison or hospital for medical study.

Kelly Beck, Cultural Resources Principal Investigator, and Kate Hovanes, Historian, from SWCA’s Salt Lake City office were both a part of uncovering the mystery behind the human skeletal remains. We asked them to talk about their experiences on the project.

Wire: How did SWCA get involved in this project?

Beck: We have a good relationship with the University of Utah and regularly help them with projects that involve architectural history and historic archaeology, so it made sense that they contacted us. We have also been helping to facilitate the University’s consultation requirements with the Utah State Historic Preservation Officer, as well as other state and federal agencies, historic preservation interest groups, and the interested public.

Wire: What made this project stand out from others you’ve worked on?

Beck: First, the revelation of human skeletal remains that prompted our project to start. It seems too much like a fictional movie plot to reveal human bones underneath the foundation of a historic building. Second, is the way that researchers from several disciplines needed to come together to tell the most complete and most compelling story possible about those bones.

Wire: Is it unusual to come into a project after construction has already started? How did you adapt?

Beck: It’s not completely uncommon for SWCA to get involved with a project when remians are newly exposed during construction. What made this project unique was the context. Here we had human skeletal remains with associated historic artifacts underneath the concrete slab foundation of a historic building.

Wire: Beyond the bones, what other artifacts and materials were unearthed?

Beck: The artifact assemblage that we recovered contained a lot of items that you’d commonly think of finding in a scientist’s laboratory. There were things like burettes,  glass test tubes, medicine bottles, and ceramic crucibles that are used in laboratories to heat chemical compounds to very high temperatures. However, there were also several artifacts that you’re more likely find in your great grandmother’s kitchen cabinets—domestic artifacts like ceramic teacup fragments, broken pieces of dinner plates, even a few buttons from clothing.

glass test tubes, medicine bottles, and ceramic crucibles that are used in laboratories to heat chemical compounds to very high temperatures. However, there were also several artifacts that you’re more likely find in your great grandmother’s kitchen cabinets—domestic artifacts like ceramic teacup fragments, broken pieces of dinner plates, even a few buttons from clothing.

Hovanes: Finding the scientific paraphernalia—beakers, flasks, crucibles, and so forth—is what helped us connect the cadavers to the medical school.

Wire: A wealth of history was reviewed to determine the story of the remains. What fascinated you the most?

Beck: This project gave us an opportunity to look at how students were trained to be medical professionals a century ago and compare that with how medical professionals are trained today. I’ve always been interested in looking at what people do and why they do it that way. I suppose that’s the main reason I’m an anthropologist!

Hovanes: My favorite area was research at the state prison. Understandably, the historic prison records aren’t something that is commonly consulted by historians; they are all hard-copy only and require considerable coordination with prison officials to grant access. Getting to look through the records was like discovering a treasure that few, if any, historians have seen before. Seeing the photographs of inmates from the turn of the century and reading about their lives was fascinating and poignant.

Wire: What surprised you most during the project?

Beck: The biggest surprise of the project for me was the location of the remains. How curious that we’d find human skeletal remains underneath the concrete slab foundation of a historic building?!

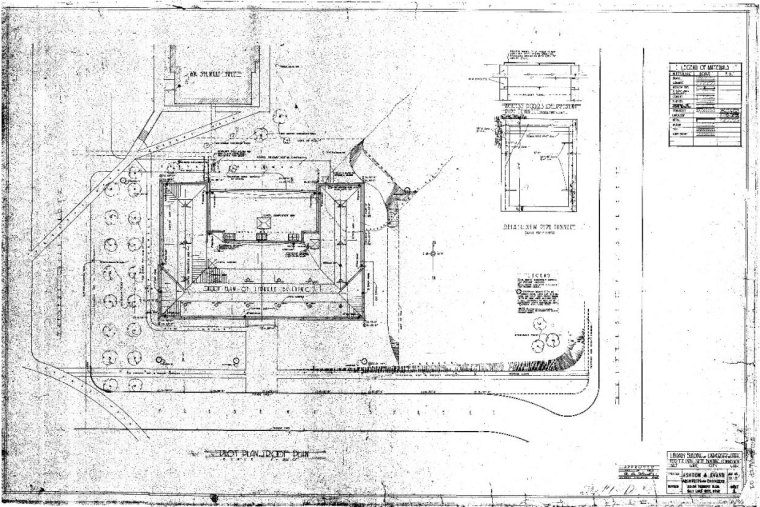

Hovanes: The different avenues of research that the project opened! We ended up looking at everything from historic photographs of President’s Circle; building plans; histories of the medical school; historic newspapers; prison records of inmates; and physical evidence, such as artifacts. We also researched different aspects of the histories of the cadavers and how they may have come to be in the ravine. We looked at everything from the history of the medical school and local hospitals, to the history of trash disposal in the United States, and the historic use of cadavers in medical schools. I’d say this is the most diverse historic research I’ve ever done.

Wire: What was your favorite part of working on this project? Least favorite?

Beck: For me, the best part of working on this project was the interdisciplinary collaboration. Individually, none of us could have put together anything like the evidence-based story that we have been able to develop from our collective research.

Hovanes: The varied research was my favorite part of this project, because I learned so much. My least favorite was the fact that ultimately, we’ll never really know what truly happened. We can make educated guesses and try to understand the factors that led to there being cadavers buried under a building, but we’ll never be able to piece together the exact events that led to it. As a historian, this is the sort of question that I’ll always wonder about.

Want to hear more of this story? In early 2018, the University of Utah’s Marketing & Communications department launched a seven-part podcast series called “Secrets of the Campus Cadavers.” Find the podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, and the RSS feed.

Wire: Can you elaborate on the importance of collaboration during the project?

Beck: Most often, projects involve only one or maybe two of the historic preservation disciplines. This project was exciting because, to tell a complete story about the people whose bones were uncovered, we needed to get pieces from archaeology, history, and architectural history. In addition, this project added the involvement of Utah’s forensic anthropologist, who analyzed the bones herself. This really was a collaborative effort between many scientists.

Hovanes: Doing the research and getting the answers the University was looking for required working with a diverse team. Doreena, the state forensic anthropologist, examined the bodies. Stephanie Lechert, a Historical Archaeologist in SWCA’s Salt Lake City office, covered the archaeology side of things with Kelly and I did the historic research with Brooke Adams, from the University, while doing research and recording the podcast. Without each of those individuals, our work would have been incomplete.

Wire: Once all the artifacts were recovered and the records were studied, what was the final determination?

Beck: All available lines of evidence suggest that the human skeletal remains found underneath the foundation slab of the George Thomas Building were likely associated with the University of Utah’s School of Medicine and were used by the school as anatomical specimens sometime between 1905 and 1920.

I think the more interesting finding though is one of cultural change and continuity. I think it’s striking that the cuts found on the century-old bones match those expected from a cadaver dissected in an anatomy lab today. The in-class experiences of medical students learning the human body hasn’t changed a whole lot. What has changed dramatically is what happens to those remains once they can no longer be used in the classroom.

Wire: What happened to the remains after the project was complete?

Beck: In keeping with the remains as a teaching tool, the bones recovered during this project have been donated to the Department of Anthropology at the University of Utah to be used as part of their human osteology teaching collection.

Wire: What can future clients learn from a project like this? Is there a takeaway message?

Hovanes: For future clients, it is useful to note that this is history, research, and public engagement done right. People would likely see historic human remains show up at a construction site and think, “Ugh, we have to keep this hush-hush.” With our help, the University of Utah was able to give some meaning to the remains and their improper disposal back in the early twentieth century. It’s a chance to educate the public, to do some solid academic work, and to right a historic wrong. Similar situations don’t have to be PR nightmares—they can be an opportunity to serve and educate the community.

Beck: Environmental consulting is what SWCA does. Our team of highly regarded cultural resources and natural resources scientists make us uniquely suited to do such interdisciplinary, collaborative research.

For more information on the Crocker detection, contact Kelly Beck at kbeck [at] swca [dot] com (kbeck[at]swca[dot]com) or Kate Hovanes at Kaitlin [dot] hovanes [at] swca [dot] com (Kaitlin[dot]hovanes[at]swca[dot]com)

Presidents Circle Photo Credit: Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah