2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

Animas-La Plata: The Water Project That Spanned Generations

Often called the “last big water project in the West,” Animas–La Plata is celebrating several milestones this year.

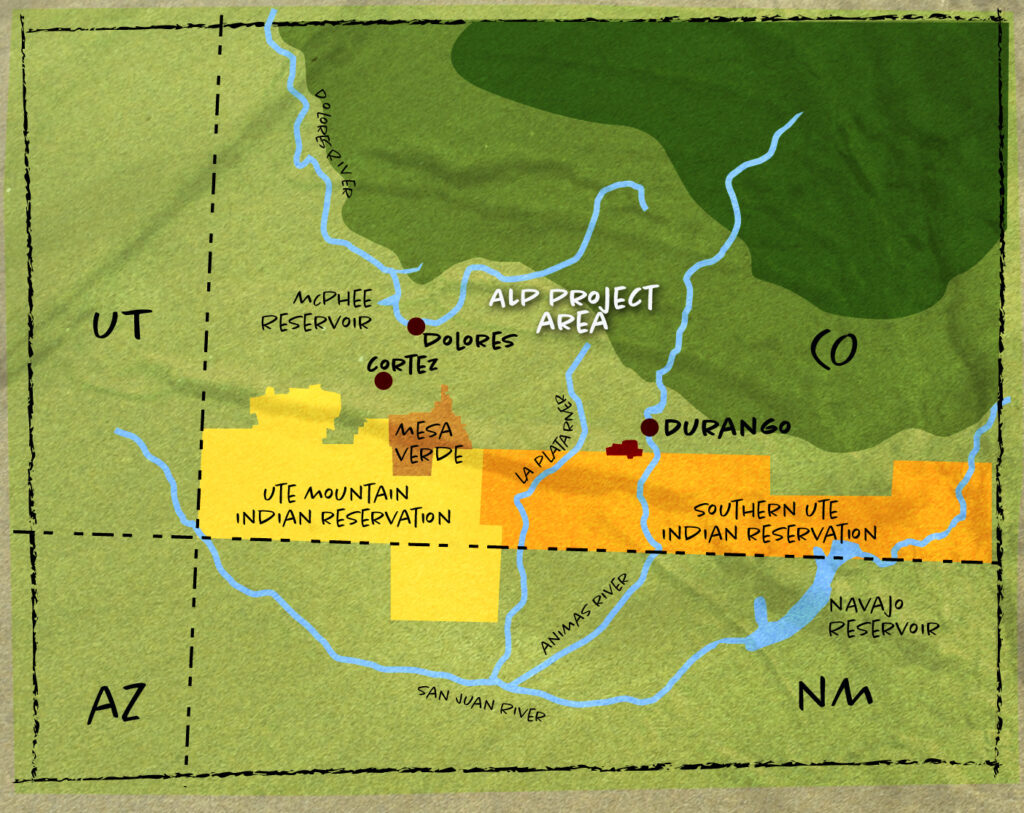

The Animas–La Plata Project (ALP) is located in La Plata and Montezuma Counties in southwestern Colorado and in San Juan County in northwestern New Mexico. Often called the “last big water project in the West,” Animas–La Plata is celebrating several milestones this year.

This May marks 10 years since the completed Lake Nighthorse reservoir near Durango began filling. To get to that point, the project survived decades of planning, collaboration, public interest, plus financial and regulatory roadblocks. Its success is due in large part to the tenacity and cooperation between tribal governments, as well as between tribes and the federal government. It’s also been a decade since SWCA completed work for the ALP.

SWCA was honored to be a part of the ALP story, having run a multi-year, multi-million-dollar archaeology project under contract with the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, cooperating with the tribe, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, backhoe subcontractors, and coordinating closely with Weeminuche Construction Authority. In light of these milestones, we wanted to look back at this landmark project and what it taught us about cultural resources investigations and water management in the West.

The scale of the archaeological investigations required for ALP made this project truly unique. SWCA was subcontracted by the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe for years of consultation and fieldwork over the landscape destined to become the reservoir, borrow pit, access roads, and other facilities. SWCA conducted archaeological investigations at 74 sites as part of the project just south of the town of Durango, Colorado. Most of the archaeological sites affected by this project were in Ridges Basin, site of the new reservoir, Lake Nighthorse (named after former U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, R-Colo.). The reservoir was created by the construction of a 270-foot-high earthen dam across a narrow canyon between Ridges Basin and the Animas River (at the intersection of Carbon Mountain and Basin Mountain). When full, Lake Nighthorse covers an estimated 1,490 acres.

Several archaeological sites were also excavated on a nearby mesa. SWCA’s excavations produced evidence of Native Americans living in the area as far back as 7500 B.C., all the way up to the European-American settlers of the nineteenth century and the most recent ranching family home of the 1950s. By far the greatest amount of data was recovered from the period called early Pueblo I, dating about 1,200 years ago, to the years A.D. 750 to 825. All of these sites were determined eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

Several archaeological crews were required to be in the Basin working simultaneously with the construction crews from Weeminuche Construction Authority. We supported consultation with Acoma Pueblo as well as the Utes, meeting regularly with tribal representatives and federal employees to be sure all legal and cultural obligations were met in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

All of the artifacts, photographs and drawings, important paper records, and the digital database from SWCA’s years

of excavations were curated at the BLM Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center and Museum (CAVM) in 2009. Learn more here

We opened and staffed a full archaeological laboratory in Durango, which not only supported the equipment and technology needs of the field staff of archaeologists, laborers, and backhoe operators, but also housed GIS technicians (creating state-of-the-art maps and graphics), a database manager, laboratory director, ceramic analysts, osteologists (human bone analysts), stone tool analysts, and other specialized scientists on staff. All artifacts were brought to our Durango laboratory, washed or cleaned by hand, and stored appropriately for analysis and cataloging. Digital photographs were downloaded and all field records were entered into a custom digital database that we built especially for this project.

One of the keys in our efficiency and success in a project of this scale was early communication and collaboration with the curation facility, the Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center and Museum (called “CAVM” for short). That is, we saw our role in the end game clearly, and early: completion of the reservoir project on time, with no costly delays from cultural resources mitigation, and proper and responsible curation of those resources in perpetuity.

Right from the beginning of the project, we worked with the staff at CAVM so that we were storing both the artifacts and the digital data in a way that could be smoothly accessioned into their database, and items would not need to be repackaged late in the game. In fact, CAVM liked our system so much that after the completion of ALP they contracted our database manager to help transfer all of SWCA’s analysis data into their system.

Our role was just one piece of the success of the ALP project. But the project as a whole sparks a larger conversation about changing approaches to water management in the West—a conversation we don’t want to lose sight of as we approach future water projects.

SWCA curated: 202,574 individual artifacts from the ALP project, project archives and paper records that cover 100 linear feet of shelf space, and a multivolume final report. This equates to at leas 315 cubic feet of artifact boxes all available for researchers by contacting the curator of CAVM.

ALP was the last reservoir project constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation, one of the largest capital works agencies in the United States. Since the Reclamation Act of 1902 (which created the Bureau of Reclamation), the federal agency has been responsible for the development of billions of dollars in water infrastructure, including dams, reservoirs, canals, and hydropower facilities.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, the biggest hurdles Reclamation faced were funding and engineering. However, changing times—especially heightened environmental awareness—have increased those hurdles to developing surface water storage. Congress authorized the development of the ALP project in 1968 and construction was completed in 2013. Within that time frame, both the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) were implemented, which added to the complexity of an already large and complex project. A final factor that created a significant challenge for new water storage throughout the West was cost. Dam construction is an expensive proposition. Environmental constraints and project costs conspired to end federal dam construction in the United States subsequent to the ALP project.

ALP provides a positive example for future water management in the West. While water conservation and new resource development are important components to mitigate the increased threat of continued drought, a holistic approach to meeting future demands may very well include new surface water storage.

ALP provides the federal government, tribes, other local communities, and environmental groups with a guide to meeting those increasing demands while appropriately addressing the legitimate concerns of preserving and enhancing cultural and natural resources. After a nearly 20-year hiatus on approval of new dam construction, Reclamation is now considering opportunities for developing new reservoirs. One of the best examples is Sites Reservoir in California’s Central Valley.

Along with new or expanded surface water storage, states and the federal government have a much larger water resources toolbox to work with. Increased groundwater storage, conservation, and reuse now offer multiple approaches to mitigate climate variability. Many of these options provide planners a much better opportunity to mitigate or avoid impacts to cultural and natural resources. However, politicians, planners, and engineers will continue to look to reservoirs to adapt to our changing—and always increasing—water demands in the arid West.

READ THE ALP REPORT: SWCA has produced 16 volumes of highly detailed data and analysis of all that was found during the project. Each of these reports (most running well over 200 pages) focuses on a different aspect of the archaeology of Ridges Basin—either the early European-American settlers of the area, or the plant remains that give us insight into the foods, clothing, and medicines used 1,000 years ago. These volumes are available through the University of Arizona Press.