2025

Comparably’s Best Company Outlook

* Providing engineering services in these locations through SWCA Environmental Consulting & Engineering, Inc., an affiliate of SWCA.

From the experts we hire, to the clients we partner with, our greatest opportunity for success lies in our ability to bring the best team together for every project.

That’s why:

At SWCA, sustainability means balancing humanity’s social, economic, and environmental needs to provide a healthy planet for future generations.

SWCA employs smart, talented, problem-solvers dedicated to our purpose of preserving natural and cultural resources for tomorrow while enabling projects that benefit people today.

At SWCA, you’re not just an employee. You’re an owner. Everyone you work with has a stake in your success, so your hard work pays off – for the clients, for the company, and for your retirement goals.

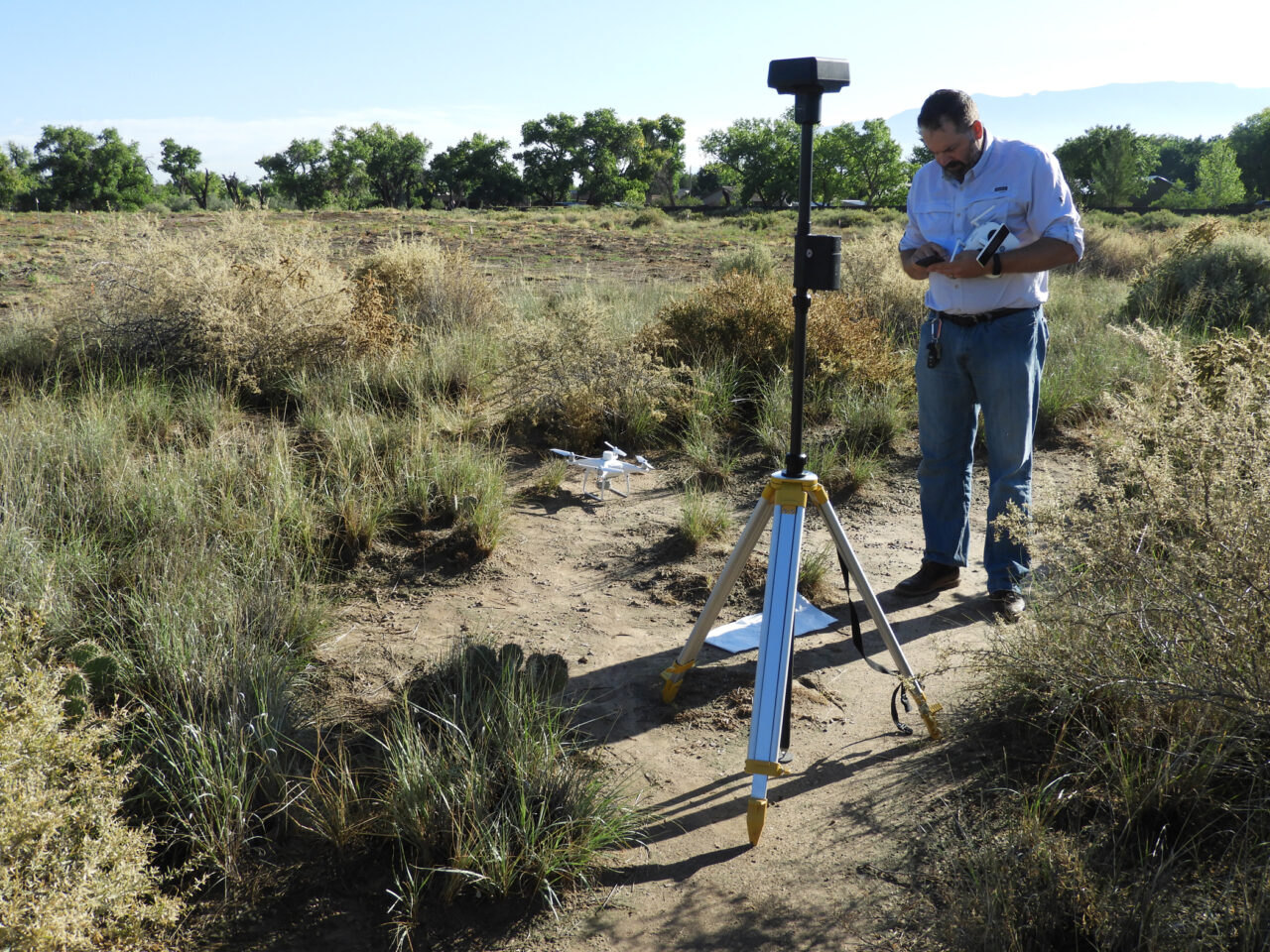

SWCA Helps Map Site of Spanish Contact-Period Battle in New Mexico

A team of archaeologists from SWCA’s Albuquerque office teamed up with geophysics surveyors to map Piedras Marcadas Pueblo in northwest Albuquerque. The location represents one of the first major battles between the 1540-1542 Spanish expedition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado and Native Americans in New Mexico.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado encountered the Tiguex (tee-wish) province during his exploration of the American Southwest, but relations turned tense in the winter of 1540-1541 and eventually, a full-scale war broke out. The Tiguex War was the earliest named war in the history of the United States. Piedras Marcadas was the Tiwa Puebloans’ final refuge, where they were able to hold off a Spanish siege for more than two months before succumbing to a complete lack of water.

SWCA assisted in the mapping to support ongoing research conducted by Matt Schmader of the University of New Mexico on land managed by the City of Albuquerque’s Open Space Division. The work was funded by a grant from the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program.

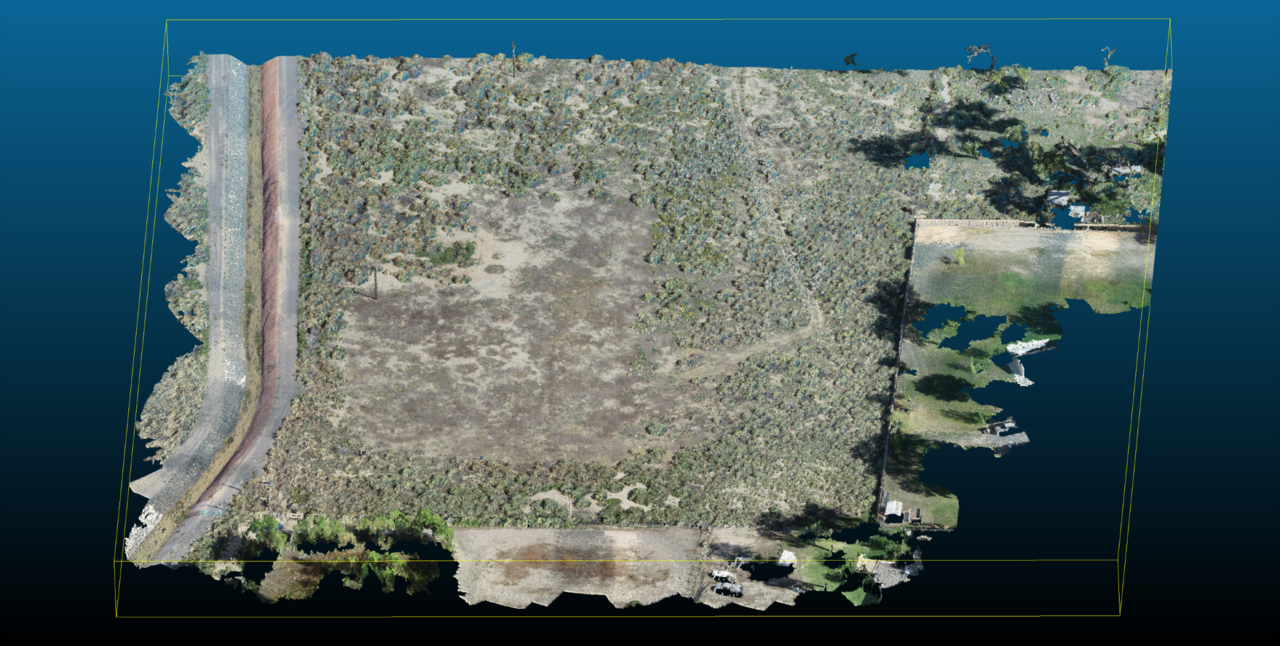

To document the structure of these important events, a team from SWCA, including Matt Edwards and William Whitehead, teamed up with local geophysical specialists Dave Decker (Southwest Geophysical, Inc., Albuquerque) and Christine Markussen (Envirosystems, Inc., Flagstaff) to perform below-ground mapping. SWCA also performed drone-based imaging and surface mapping, producing a site-wide image and 3D digital elevation model of the site area. The team was able to locate subsurface archaeological features, such as adobe wall outlines, that complete the map of this site.

“The benefits of using remote sensing are many,” says Matt Edwards, SWCA’s New Mexico/Four Corners Vice President. “We can get an idea of archaeological structures, define areas of human activity, and rule out areas where there are no signs of activity.”

Point cloud of Piedras Marcadas

The remote sensing was crucial to understanding the layout of the embattled pueblo, which was once one of a dozen thriving villages in the middle Rio Grande valley. This type of research does not harm archaeological resources and can be done repeatedly in combination with other techniques, unlike conventional archaeological research that destroys the resource in the process of data collection.

“The geophysics done by SWCA and their experts added immeasurably to understanding the locations of walls and how events unfolded at the site,” added Matt Schmader.